Philippine Online Casinos: Continue Playing or Game Over?

Marcos set to weigh fate of controversial sector opposed by China.

KAWIT, Philippines — In a casino on Island Cove, south of Manila, Filipino women in bright red minidresses sit behind tables dealing out cards for baccarat and Dragon Tiger. The only thing missing from the scene? The customers.

That is because Island Cove, sitting on 48-hectares of a former leisure park and wildlife sanctuary, is at the heart of Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, or Pogo, industry. The women do their dealing in front of cameras, while online wagers pour in from overseas, many from China.

It is an industry that has generated jobs and billions of dollars in revenue, benefiting businesses from real estate to retail. Once a dormant property, Island Cove now boasts 20 residential and office towers, villas, restaurants and retail shops serving the thousands of workers that keep the gaming operations running.

But Pogos have also attracted controversy and opposition among lawmakers.

At issue is whether the benefits of the industry outweigh the crime and corruption that have sprung up around them. China, whose citizens have been lured into Pogos to either work or bet, frowns on the sector, while analysts say the issue is down to domestic vested interests.

The Philippine Senate for months investigated Pogos. In March, Sherwin Gatchalian, a senator who led some of the hearings, announced his conclusion: “The Pogo industry has proven to be more of a liability than an asset to the Philippine economic and social order.”

Gatchalian called for the industry’s permanent shutdown, but many of his peers have yet to back his drastic proposal. The decision now falls to President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., whose administration is also divided on the issue.

Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno, who had branded Pogos “reputational risks,” said last month he was still opposed to them.

“If I am asked, I will give my recommendation [to the president],” Diokno told reporters.

Manila’s anti-dirty money council — which Diokno previously chaired as central bank chief — in 2020 found Pogos were prone to “money laundering and financial crimes.” Weeding them out would boost the Philippines’ bid to exit the “gray list” of the Financial Action Task Force, a global financial crime watchdog, Diokno said.

Pogos, which cater to foreigners betting remotely, flourished under former President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration, which introduced regulations for the industry in 2016.

This policy dovetailed with his efforts to court Chinese investors and tourists. State regulator Philippine Amusement and Gaming Authority or Pagcor issued dozens Pogo licenses to companies, many of them domiciled in the British Virgin Islands. Licensees in turn sought service providers, like those in Island Cove, to provide the games and manpower that propelled the industry.

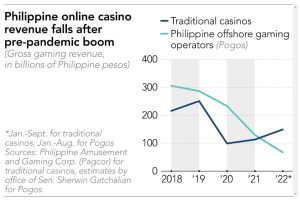

In 2018, two years after the Philippines embraced online casinos, Pogos generated 305.7 billion Philippine pesos ($5.5 billion) in gross gaming revenue, based on estimates by Gatchalian’s office. In contrast, traditional casinos booked 215.8 billion pesos that year, Pagcor data shows.

Image source: https://asia.nikkei.com/

The industry’s explosive growth was driven by a massive influx of foreign workers, mostly Chinese, who via messaging apps like WeChat, enticed their compatriots abroad into playing on gaming sites run by Pogos. As the industry spawned problems in China, where gambling is prohibited, online casino havens Cambodia and the Philippines came under pressure from Beijing. Cambodia’s Hun Sen obliged with a crackdown, but Duterte did not.

The Philippines struggled to regulate the industry. Pogos under-declared revenue to evade taxes, Gatchalian said. Chinese workers bribed local immigration officers at the Manila airport for easier entry. Chinese kidnapped fellow Chinese, while dozens found themselves embroiled in prostitution and human trafficking.

But border closures during the pandemic and a heftier tax burden prompted many to close shop or move elsewhere in Southeast Asia or to the Middle East. The number of Pogo licensees had shrunk to 34 in 2022 from 59 in 2019. From an estimated half a million workers at its peak, Pagcor said the industry employed 47,488 last year, half of them Filipinos. Industry insiders estimate the head count is still five times higher.

As the Philippine Senate began a probe of the sector last year, China’s embassy in Manila said, “Pogos should be tackled from the root so as to address the social ills in a sweeping manner.”

Marcos has yet to publicly comment on Gatchalian’s call for a permanent ban. But in January, the president favored a review of the industry. “The legal ones pay their bills … those videos showing killings, they are the illegal ones,” Marcos said.

There has also been a pushback within the Marcos administration against an outright ban.

Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla, whose agency has deported Chinese Pogo workers, told reporters: “If it’s legal, we tolerate it. If it’s illegal, we arrest them and deport them.”

Remulla’s family used to own Island Cove resort and sold the property in 2018 to ethnic Chinese investors. He said they no longer have interests there, but he was wary of people losing their jobs, including those from his home Cavite province.

David Leechiu, head of Leechiu Property Consultants in Manila, said Pogos still occupy roughly a million square meters of office space, down from 1.7 million sq. meters before the pandemic. “The industry will get hurt big time [if Pogos are banned],” Leechiu said.

Conglomerate-backed real estate developers like Ayala Land, SM Prime, and Megaworld, once major beneficiaries of the Pogo office rental windfall, as well as real estate investment trusts DDMP and Filinvest, have cut their exposure in the industry amid uncertainties.

However, Leechiu said there are still companies that believe they can continue operating in the Philippines, and plan to expand offices.

First Orient International Ventures, which runs the Island Cove hub, said the industry should be policed, not phased out. The company told Nikkei Asia that half of the 10,000 workers in the hub are locals, including maintenance staff and clerks, and that “fly-by-night operators are the ones causing menace to a good and productive industry.”

PAGCOR has also rejected the proposal to ban Pogos while vowing to tighten regulations. “The application [for licenses] is open,” chairman Alejandro Tengco said last month.

Alvin Camba, a University of Denver assistant professor who has closely studied the industry, said the impasse over Pogos is down to politics and vested interests, factors that will likely complicate Marcos’ decision.

“Many of those who benefited from Pogo, particularly Philippine businesses who own the service providers of Pogos, are also campaign contributors to people in the administration,” Camba said. “As such, some people in the administration would like to keep online gambling firms in the country.”

Article Source

https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-Spotlight/Philippine-online-casinos-Continue-playing-or-game-over

Other Interesting Articles

NBA: Ja Morant Keeps Grizzlies Alive as Lakers Beaten

NBA: Ja Morant Keeps Grizzlies Alive as Lakers BeatenApr 27, 2023